Brief Biography of John Nost II d.1729.

Lifted entirely from

John

Nost II was the cousin of John Nost I, and ran the family workshop until 1729.

His business was chiefly in lead garden figures, but also included a number of

large-scale equestrian statues of George I.

Nost I left his cousin £50 in his will and an extra £10 ‘towards discharging’

his debts, which suggests that the young man began his adult life

inauspiciously. Nost II continued to pay rates for the property previously

occupied by Nost I in Stone Bridge, near Hyde Park, from September 1710, and he

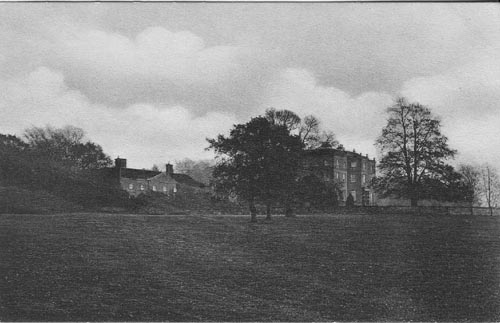

managed to retain some of Nost I’s patrons, including Sir Nicholas Shireburn of

Stonyhurst, who bought several garden figures in 1714 and 1716 (3, 4). Among

his new clients was Edward Dryden of Canons Ashby (2), who owed the sculptor

£65 5s for a gilt gladiator in 1713 (Nost II/Dryden).

Little is known of his family background, except that he had a sister called

Mary Butler (or Buller), who was mentioned in Nost I’s will. He married

Catherine Cheesborough at St Martin-in-the-Fields in 1708 and they already had

two children in 1710, both of whom received £5 in his will. One of these,

another Catherine, was baptised at St Martin’s on 27 March 1710.

Frances Nost, the widow of Nost I, died in 1716, leaving Nost II ‘all the

marble goods and figures at his house which belongs to me’. She also released

him from ‘all debts and moneys from him to me due and owing at the time of my

decease’, which suggests that his fortunes had not improved.

By 1717 the business was evidently prospering, for Nost received a commission

for a bronze statue of King George I from the corporation of Dublin (12). They

agreed in that year to pay the sculptor £1,500, and a part-payment of £500 to

‘Mr John Noast of London, statuary’ was made in August 1721. Nost cast the

figure of the horse from moulds made from Le Sueur’s statue of King Charles I

at Charing Cross, and went on to use the cast to produce several more lead

versions for other patrons, including the extravagant Duke of Chandos, whose

gilded statue with a handsome pedestal carved with trophies of war, was erected

at Canons (Canons Grand Inventory). The statue, which terminated a vista in the

gardens, was singled out for appreciative comment by an anonymous Frenchman

visiting in 1728.

Nost may have provided several other figures for Canons: the

1725 inventory includes, for instance, such parapet figures as Courage

represented by Hercules with his club, History with a table & pen in her

hand, and Fame sounding a trumpet, all subjects associated with the Nost

workshop. Several Whig patrons followed the Duke’s example and Nost’s workshop

became associated with equestrian figures of George I, presented as a

conquering hero in plate armour and crowned with laurels. A very similar image

in lead appeared outside the market hall in Gosport (8), there was a gilt

version in Grosvenor Square that cost £260.19s (17), and two leading figures in

the Whig ministry, Lord Cobham and the Duke of Bolton, advertised their

political allegiance with versions of the statue sited in pivotal positions at

Hackwood and Stowe (11, 16).

In 1716 Nost took over another property from the sculptor Edward Hurst, next to

his premises in Stone Bridge. The two buildings were rated at £12 and £18

respectively. By 1720 one of them was vacant and in 1722, Nost’s name

disappeared from the Stone Bridge rate books. He paid annual rates of £20 from

1720 until his death in 1729 on another property, a yard in neighbouring

Portugal Row.

In April 1718 Nost made an agreement with Sir John Germaine to supply to

Drayton House, Northants ‘two leading Statues Six footh hey from the plint, one

a [...] for a [...] and the Other figur a backus according to the patrons

showed to the Sd. Sr. John, and also to make three Leadin Vasis upwards of four

footh high of two Severall Sorts’ (24). He also agreed that ‘the Sayd figurs

and Vasis Shal be painted twice over with a White Stone colour’. The price set

for this commission was £40 and Nost’s signed receipt, dated 27 May 1718,

records the supply (Drayton Archive MM/A/723). Another paper in the same

archive headed ‘quitance de Mr. Nost Statuaire’ records the above payment and

date as well as other charges for porterage, with an intriguing payment of one

guinea ‘a la femme francaise’. An earlier receipt in the Drayton Archive

labelled ‘Quitance des vases’ headed London and dated 6 October 1710 but with

an indecipherable signature is for twelve vases costing £60 (ibid, MM/A/675).

This almost certainly refers to lead vases above colonnades in the courtyard at

Drayton, for which there are bills, also dated 1710, which the mason John

Woodall, who had earlier worked there for the architect William Talman, was

building. Today there are only eight vases. The London heading for the receipt

suggests that this also refers to the Nost yard.

Further evidence of John Nost’s ability to retain Nost I’s patrons comes from

two contracts drawn up eight years after his elder cousin’s death. These were

for lead statues for the 1st Earl of Hopetoun’s gardens at Hopetoun House, near

Edinburgh. The first contract, dated 24 May 1718, was for four metal statues,

Cain and Abel, Diana, a Gladiator and Hercules with a club, at a cost of £86.

The second, dated 20 June 1718, was for Adonis with a greyhound, Venus with

Cupid, Venus coming out of the bath, and Phaon playing on a pipe (7). These

were to cost £56 (Nost/Hopetoun MS). The contract says Nost was to deliver the

first statues to Scotland ‘by the latter end of July next’ and the second batch

was to arrive by 1 October. Surprisingly, the goods did not arrive until 16

September 1719 and this is confirmed by a shipping order, dated 28 February

1719, for ‘fave larg’ casses of Leaden status’ with a freight charge of one

guinea to cover the journey from London to Leith (Nost/Hopetoun MS) and a

receipt accepted by ‘Mr. John Nost’ for the total of the two contracts, £142,

dated 14 September 1719 (Nost/Hopetoun MS). The only statues from the large

number named in the 1709 estimate sent by John Nost I were the Bacchus and

Ceres. None of these works remain at Hopetoun.

The Duke of Chandos called him back to Canons in 1723 to inspect some vases

which appeared to be in danger of falling from the parapet. Chandos paid him

£480 10s between 1722 and 1725, probably for vases and lead figures in the

extensive pleasure-grounds. He also provided a statue of George II, ordered at

the time of the King’s accession in 1727. This was sold at the Canons auction

in 1747 and erected in Golden Square in 1753 (18).

One of Nost’s last works, his only known monument, celebrates Joseph Banks and

was erected at Revesby, Lincs, shortly before the sculptor’s death (1). A

letter from Nost to Banks’s son refers to an order for chimneypieces and

concludes ‘I desire to know whether I can have the picture of your father, for

I am going on with the monument, and the head will take more time in finishing,

for the more time I take in doing itt the better it will be completed’ (Hill

1952, 93).

He died in April 1729, and two obituaries survive. The Political State of Great

Britain recorded ‘Sunday the 27th, died Mr Nost, a famous Statuary, at his

House near Hyde-Park Corner’ and The Historical Register announced ‘Dyd Mr

Nost, a noted Statuary’. The administration of his will was granted to his

widow Catherine Nost on 23 May 1729. His son, John Nost III (often known as

‘the younger’) was at that time apprenticed to Henry Scheemakers.

Nost appears to have been the man referred to by Vertue as a nephew of Nost I,

‘who drove on the business but never studied – nor did himself anything

tolerable’ (Vertue IV, 35). If so, this is a harsh judgement to pass on a

sculptor who successfully ran the family workshop for 19 years and provided

memorable iconic portraits of the first Hanoverian king. Nost was confused with

his cousin John Nost until the recent discovery of his will and posthumous sale

catalogue. To add to the confusion Musgrave’s Obituary mistakenly indexed him

with the forename Gerard.

BB/MGS

Literary References: Northampton Mercury, 13 Dec 1725; PSGB, v38 (1729), 425;

Voyage d’Angleterre, 1728; Hist Reg, v14, (1729), 28; Vertue IV, 35; Musgrave

1899-1901, IV, 309; Hill 1952, 93; Webb 1957 (3), 119; Stonyhurst 1964, 479;

O’Connell 1987, 802-6; Davis 1991 (1), passim; Grove 23, 1996, 253-4 (Murdoch);

Spencer-Longhurst 1998, 31-40; Jenkins 2005, 64; Sullivan 2005, 8

Archival References: WCA, Highways Rate, 1710 (F5311-2); Poor Rate 1712,

(F3574); Poor Rate 1716, (F3597), Highways, 1722 (F5550); Nost II/Dryden; Nost

II casting warrant; Voyage d’Angleterre, 1728; Canons, Accounts with Tradesmen;

Nost/Hopetoun MS; Canons Grand Inventory; Chandos catalogue, June 19, lot 57,

June 26, lots 54-61; IGI

Wills: John Nost I (proved 12 August 1710 LMA, Archdeaconry of Middlesex, AM/PW

1710/89); Frances Nost (proved December 1716, FRC PROB 11/555/fols 195v-196v);

John Nost’s Admin, 23 May 1729 (FRC PROB 6/105 fol 95)