Sir William Fermor (1621 - 1661) and his wife Mary (d. 1670).

of Easton Neston

of Easton Neston

A Pair of Plaster Busts.

Attributed to Peter Besnier (d. 1693).

Part 2 of a brief look at the works of the Besnier family .

Sold at Sotheby's Easton Neston sale Lot 12 - 17th May 2005.

Part 2 of a brief look at the works of the Besnier family .

Sold at Sotheby's Easton Neston sale Lot 12 - 17th May 2005.

Bought with the aid of an Art Fund grant by Northampton Museum and Art Gallery.

Entry below from The Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors available online at -

Peter Besnier (Bennier) - A French sculptor and the brother of Isaac Besnier,

who had collaborated with Hubert le Sueur on the monument to George Villiers,

1st Duke of Buckingham, erected in Westminster Abbey in 1634. Peter Bennier may

have been trained in France but was living in England before October 1643, when

he was appointed sculptor to King Charles I. He was required to look after the

‘Moulds, Statues and Modells’ in the Royal collection, a duty previously

performed by his brother, in return for the use of a house and £50 pa from the

privy purse.

The Civil War prevented him from taking up his duties and he was

deprived of his office during the Commonwealth. At the Restoration he

petitioned to be reinstated on the grounds that the late King had granted him

the ‘place of sculptor to His Majesty and the custody of his statues, etc, but

by reason of the most unhappy distraction befallen since, hee injoyed not the

same place, but was reduced into very great poverty and want through his

faithfulness and constancy’ (TNA SP 29/2, no 66-1, quotedby Faber 1926, 14).

His request was granted on 15 March 1661 (TNA, LC3/25, 113, cited by Gibson

1997 (1), 163) and he held the post until his death, when he was succeeded by

Caius Gabriel Cibber.

Bennier is listed as a ratepayer of Covent Garden,

1649-51, and among the Ashburnham Papers is a reference to a tenement occupied

by Bennier near Common Street in 1664 (LMA, ACC/0524/045,046,047, 048, cited by

Gibson 1997 (1), 163).

It has been tentatively suggested that he worked for

Hubert le Sueur. He signed the monument with a ‘noble’ portrait-bust to Sir Richard

Shuckburgh (1) (Gunnis 1968, 50).

The monument to Sir Hatton Fermor at Easton

Neston, Northants, has been attributed to him because the bust is similar to

the Shuckburgh one and the two families had intermarried.

In 1655 Bennier was

employed at Lamport Hall, Northants, carving shields and ‘pictures’, which were

probably statues (Northants RO, IL 3956, cited by White 1999, 11, 12 n 10-11)

(2). He also did unspecified work for the crown at Somerset House in 1661-2.

Literary References: Gunnis 1968, 50; Colvin V,

1973-6, 255; Whinney 1988, 90, 93, 439 n 16, n 21, 440 n 2-3; McEvansoneya

1993, 532-5; Grove 3, 1996, 875 (Physick); White 1999, 11-12

Attention should be paid to the form of the socles - variations of which appear on English and Netherlands busts of the 17th century.

Photograph Courtesy Sotheby's.

see - http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.12.html/2005/sale-at-easton-neston-l05500

The Sotheby's Catalogue entry for these busts follows below -

The Sotheby's Catalogue entry for these busts follows below -

A pair of plaster busts of Sir William Fermor, 1st bt.

(1621-1661) and his wife Mary (1628-1670), daughter of Hugh Perry, attributed

to Peter Besnier (French, d.1693),

1658.

He wearing quirass with lions pauldrons and a sash

tied on his right shoulder, his hair falling in locks over the breastplate, an

old illegible paper label to the reverse; she facing slightly to dexter, her

hair styled in deep curls about her bare upper chest and shoulders; each set on

integral plaster socles bearing the date 1658.

he 72cm., 28½in.; she 65.5cm., 25¾in.

These plaster busts are notable survivals of 17th century English portrait sculpture and represent important additions to the small corpus of known works executed by the French-born artist Peter Besnier, Sculptor-in-Ordinary to Charles I and later Charles II. They have never been previously published.

The attribution rests on physiognomic and stylistic comparisons as well as contextual evidence. The expressive modelling of the heads with their animated features are more advanced than the work of Besnier’s predecessor as Court Sculptor, Hubert Le Sueur, whose portraiture has been rightly criticised for having a ‘curiously inflated appearance’. The angle of the heads are more accentuated than the iconic frontality found in Le Sueur’s busts. In their sense of movement they are much less mannered and the richly modelled sash, drapery and hair - notably to the bust of Mary - imbue them with a liveliness derived from the Italian Baroque.

In this connection one might at first think of two other sculptors active in Caroline England, namely the Italian, Francesco Fanelli (1577-after 1641) and the Fleming, Francois Dieussart (c.1600-1661). Whinney, who was the first to raise the possibility that Besnier may have been the sculptor responsible for the Easton Neston busts, observed that they were ‘closer to the style of Dieussart’ (op.cit. p.440, note 2). There is no specific comparison to be made in support this hypothesis, unless Whinney was alluding to their advanced baroque naturalism: Dieussart was perhaps the most talented of the foreign sculptors lured to London having spent the years 1622-1630 in Rome assimilating the latest developments in Baroque sculpture.

However Dieussart had departed for The Hague in 1641, well before the Easton Neston busts could have been modelled, and the same year also marks the last recorded reference to Fanelli in England.

It is Peter Besnier’s elder brother Isaac (active 1631-c.1642) who therefore provides the point of departure for a meaningful stylistic comparison, and one that can be seen to reinforce Whinney’s initial, if instinctive, placement of the busts in the Besnier orbit.

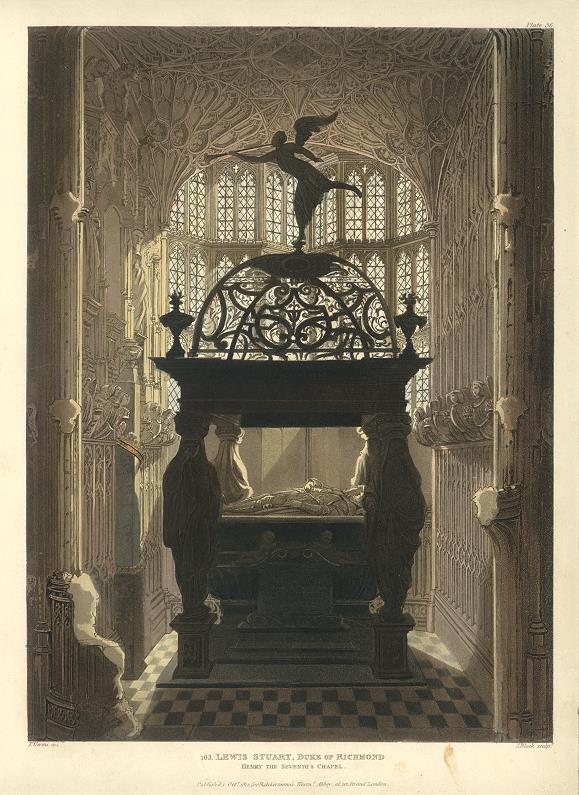

Isaac Besnier was first employed to look after the ‘Moulds, Statues and Modells’ in the royal collection but his major sculptural contribution is to be found in the realm of monumental tomb sculpture of the 1630’s. He collaborated with Le Sueur on the tombs of three of the greatest personalities of the Caroline Court: that of the Earl of Portland in Winchester Cathedral; and those of the Duke of Buckingham and the Duke of Richmond and Lennox in Westiminster Abbey. While Le Sueur cast the figures and effigies in bronze, Isaac carved the architectural marble components, including the statuary and tablets. Indeed Lightbown credits him for a significant part of their overall design. It is interesting to hypothesise how the commission for the busts came about. Each portrait bears the date 1658, an inauspicious time for sculptor and patron alike.

The attribution rests on physiognomic and stylistic comparisons as well as contextual evidence. The expressive modelling of the heads with their animated features are more advanced than the work of Besnier’s predecessor as Court Sculptor, Hubert Le Sueur, whose portraiture has been rightly criticised for having a ‘curiously inflated appearance’. The angle of the heads are more accentuated than the iconic frontality found in Le Sueur’s busts. In their sense of movement they are much less mannered and the richly modelled sash, drapery and hair - notably to the bust of Mary - imbue them with a liveliness derived from the Italian Baroque.

In this connection one might at first think of two other sculptors active in Caroline England, namely the Italian, Francesco Fanelli (1577-after 1641) and the Fleming, Francois Dieussart (c.1600-1661). Whinney, who was the first to raise the possibility that Besnier may have been the sculptor responsible for the Easton Neston busts, observed that they were ‘closer to the style of Dieussart’ (op.cit. p.440, note 2). There is no specific comparison to be made in support this hypothesis, unless Whinney was alluding to their advanced baroque naturalism: Dieussart was perhaps the most talented of the foreign sculptors lured to London having spent the years 1622-1630 in Rome assimilating the latest developments in Baroque sculpture.

However Dieussart had departed for The Hague in 1641, well before the Easton Neston busts could have been modelled, and the same year also marks the last recorded reference to Fanelli in England.

It is Peter Besnier’s elder brother Isaac (active 1631-c.1642) who therefore provides the point of departure for a meaningful stylistic comparison, and one that can be seen to reinforce Whinney’s initial, if instinctive, placement of the busts in the Besnier orbit.

Isaac Besnier was first employed to look after the ‘Moulds, Statues and Modells’ in the royal collection but his major sculptural contribution is to be found in the realm of monumental tomb sculpture of the 1630’s. He collaborated with Le Sueur on the tombs of three of the greatest personalities of the Caroline Court: that of the Earl of Portland in Winchester Cathedral; and those of the Duke of Buckingham and the Duke of Richmond and Lennox in Westiminster Abbey. While Le Sueur cast the figures and effigies in bronze, Isaac carved the architectural marble components, including the statuary and tablets. Indeed Lightbown credits him for a significant part of their overall design. It is interesting to hypothesise how the commission for the busts came about. Each portrait bears the date 1658, an inauspicious time for sculptor and patron alike.

Sir William Fermor was the elder son of Sir Hatton Fermor and his wife Anne Cockayne. At the outbreak of the Civil War he and his younger brother Hatton joined the King. William was created a baronet by King Charles 1641: his younger brother was less fortunate dying for the Royalist cause at Culham Bridge in 1645. Sir Williams's marriage was very much a reflection of his loyalties. His wife Mary Perry was the widow of the Hon. Henry Noel who had died a prisoner of the Parliamentarians. His brother Baptist Viscourt Campden was a colonel in the Royal Horse Regiment.

During the years of the Interregnum Sir William had had to compound for his estate and was under constant suspicion of agitation. In 1653 he was summoned before the council and in 1655 he was accused of killing the Protector’s deer. In 1658, the year of his portrayal, he was publicly listed as a Northamptonshire royalist without military rank. Besnier too suffered hardship, having been deprived of his office of court sculptor, which he had held since 1643, by the Parliamentarians. In his petition for reinstatement at the Restoration, he claimed that he had fallen into ‘very great poverty and want’ (see White op.cit.). However the evidence suggests the opposite was true. In 1655 he was carving statues and shields for John Webb’s revisions to Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire (not far from Easton Neston) and in the following year, 1656, he was working on his only signed and securely attributed work, the monument to Sir Richard Shuckburgh, just across the border in Warwickshire. These commissions, together with the present plaster busts, perhaps intended as presentation models for finished bronzes, show that Besnier was not as close to the ‘great poverty’ he claimed to be. If it was not his work at Lamport that brought him to the attention of Sir William, it must have been owing to the Shuckburgh monument that artist and patron became acquainted. Sir William’s sister Katharine was married to Sir John Shuckburgh, Sir Richard’s son and heir (see White op.cit., p.12), which provides a convenient avenue for their introduction.

Whinney, followed by White, attributes the posthumous monument to Sir Hatton and Lady Fermor in St. Mary’s Church, Easton Neston, to Peter Besnier. The memorial also commemorates Sir William, whose marble bust appears between the two figures of his parents. This bust bears no relation to the present plaster and is of a much inferior standard of execution. The general design of the monument, with its three effigies of Sir Hatton’s daughters arranged at the very top, recall his brother Isaac’s work of the 1630’s for the Earl of Portland. The tablet inscription nonetheless dates it to 1662, a year after Sir William’s death and at a time when Peter Besnier is documented in London working in his court capacity at Old Somerset House.

Whinney notes that the only signed monument by Peter Besnier - the monument to Sir Richard Shuckburgh d. 1656 at Shuckburgh, Warwickshire is similar in style to the Fermor monument at St Mary's Church Easton Neston, Northamptonshire (see below) - the two families were related by marriage.

I have not yet been able to locate a good photographs of either of these monuments.

The paragraph below from British History online from - A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 6, Knightlow Hundred. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1951.

The south chapel (12 ft. 6 in. by 9 ft. 2 in.) is similar to the one on the north. Against the east wall is a large marble memorial to Richard Shuckburgh, died 1656. It has a classic pediment with the Shuckburgh coat in the tympanum, surmounted by three urns, and below a portrait bust flanked by angels with trumpets holding back curtains. Underneath there is a carved panel with inscription, under a pediment of scrolls with a skull on either side. It rests on a carved splay and a moulded base, with a block in the centre of the moulding on which is placed a skull, below it the name Pet. Bennier.

Whinney, followed by White, attributes the posthumous monument to Sir Hatton and Lady Fermor in St. Mary’s Church, Easton Neston, to Peter Besnier. The memorial also commemorates Sir William, whose marble bust appears between the two figures of his parents. This bust bears no relation to the present plaster and is of a much inferior standard of execution. The general design of the monument, with its three effigies of Sir Hatton’s daughters arranged at the very top, recall his brother Isaac’s work of the 1630’s for the Earl of Portland. The tablet inscription nonetheless dates it to 1662, a year after Sir William’s death and at a time when Peter Besnier is documented in London working in his court capacity at Old Somerset House.

_____________________________________

Whinney notes that the only signed monument by Peter Besnier - the monument to Sir Richard Shuckburgh d. 1656 at Shuckburgh, Warwickshire is similar in style to the Fermor monument at St Mary's Church Easton Neston, Northamptonshire (see below) - the two families were related by marriage.

I have not yet been able to locate a good photographs of either of these monuments.

The paragraph below from British History online from - A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 6, Knightlow Hundred. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1951.

The south chapel (12 ft. 6 in. by 9 ft. 2 in.) is similar to the one on the north. Against the east wall is a large marble memorial to Richard Shuckburgh, died 1656. It has a classic pediment with the Shuckburgh coat in the tympanum, surmounted by three urns, and below a portrait bust flanked by angels with trumpets holding back curtains. Underneath there is a carved panel with inscription, under a pediment of scrolls with a skull on either side. It rests on a carved splay and a moulded base, with a block in the centre of the moulding on which is placed a skull, below it the name Pet. Bennier.

Sir William Fermor purchased some of the Arundel Marbles - those not in the Ashmolean.

Guelphi was employed in the 1720's to restore (or some might say mutilate) them.

___________________________

The Monument to Sir Hatton and Lady Fermor at St Mary's Easton Neston is attributed to Peter Besnier

St Marys Church

Easton Neston

Towcester

Northamptonshire

NN12 7HS

Telephone: 01327 350459 Email:

office@tovebenefice.co.uk Access through Easton Neston Park via Hulcote

The church is normally locked. Access is through The

Towcester Benefice Office 01327 350459

________________________________________

.jpg?height=400)